I Want More Bass AND I Want It Loud!

The esthetics of recorded music have changed a lot since the advent of digital recording and, at the same time, the way we expect music to sound has evolved quite a bit over the last 30 years. We expect to hear a lot more bass coming out of our speakers than our parents used to. If you need proof just compare some heralded recording of the 60s or 70s (Skip the 80s, they were high that decade) to some decent modern recording on a familiar speaker system. If you are still not sure, ask yourself what sounds heavier: Barry Manilow coming out of a 76' Chevette or JayZ coming out of an 08' Escalade?

Everybody wants lots and lots o' bass in their tracks these days and everybody wants everything to be loud, but it's very hard to achieve both. But why, oh why?

The key is to realize that not all frequencies have the same kind or amount of energy. Let's keep it simple and think of 'energy' as just plain 'level'. You'll find that the low end of a track will take more actual level to create the same apparent loudness than the high end will. In other words the lower end of your frequency range takes up the most room in your mix.

Really? Yup.

Try this for yourself: take a well balanced Hip-Hop or R&B-ish style mix (you have one of those, right?) and look at your average level meter (you have one of those too, right?). Now mute the vocal and look at its impact on the meter, then mute the bass drum and look at its impact on the meter. So?

Right, the meter drops a lot more when you mute the bass drum even though the vocal seems louder or more present. (If you can't see it because you only mix accapella records, see me after class). This is especially crucial to pay attention to when setting up compressors and limiters. Since the low-end energy is more prominent, the processors tend to respond to it more than to the high end energy. I often hear: "hey man, can you compress the hell out of the bass to make it fat?" To which I usually answer "Do you want it compressed or do you want it fat?"

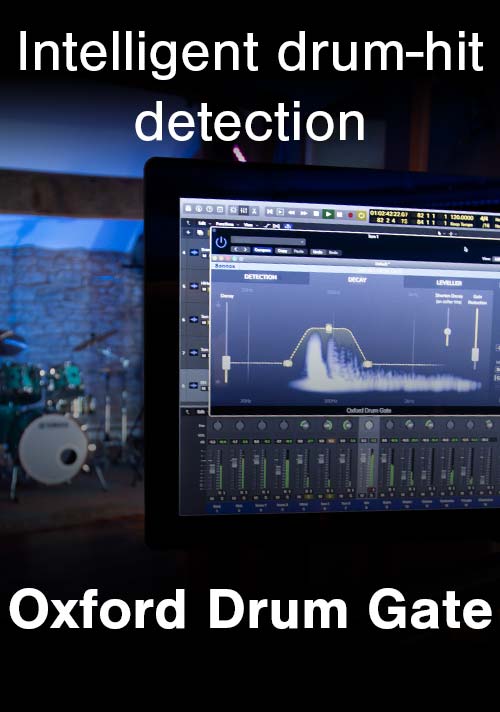

Again try this for yourself: Take a reasonably well recorded electric bass, put the compressor from the Oxford Dynamics on it and hit it hard (Set it for 4.1 ratio, 4 ms attack, 4 ms release, then lower the threshold until you get 10dBs-ish of reduction). Make sure that compressed and uncompressed signals are at the same level using the makeup-gain knob and then compare them using the main bypass switch. What do you find? You'll probably find that the sound is more even-leveled but that there is less low end. That's because a compressor is designed to take things that are loud and make them softer, so if the low end is the loudest thing then it's going to be hit harder and get softer. Staggering isn't it?

So how do you deal with this tragic state of affairs?

First: be careful with your compression habit, it'll kill you in the end.

Otherwise: you can use sidechain techniques to preserve your low end while compressing.

Here's how you do it: Go back to your bass track and your Oxford Dynamics. Is it still nice and squished? Perfect. Now activate the Sidechain-EQ module and dial DOWN the bass (set the eq to cut -10dB around 220Hz or something like that, activate the shelving and the SC-EQ switch). So now the compressor takes its cue from the EQ'd signal but still processes the clean signal. Pause and think about that for a second... What you are doing is telling the compressor "Hey dude", (or "hey mate" if you are British) "I'm sending you a version of the signal that has the stuff I actually want you to compress. There is no bass in that version, so please don't react to the bass anymore. Ok?"

You'll see that the level jumps up considerably when you activate the Sidechain circuit and squishes back down when you don't. That's because the compressor, being blind-sided by the EQ'd sidechain you are sending to it, is no longer clamping down on the bass energy when the sidechain is enabled. Et voila, as we say. You may also notice that this kind of compressor setting (used in moderation) gives you a really controlled, yet fat, bass sound compared to the uncompressed version. Isn't that wonderful?

Ah, but what of our 'fat versus loud conundrum'? Well, we got slightly side-tracked, but as a teaser until next time, think of it this way: how many elephants can you fit in a fixed size room? There comes a point where cramming more elephants in a room that can't handle them is going to generate some funny noises. It's quite the same with your mix.

Fab French born, currently residing in NYC - has been playing, writing, producing and mixing music in studios all over the world, from Paris to New York and Brussels to Boston. Recently, at his studio in the East Village of Manhattan, Fab has worked on records for Jennifer Lopez, Mark Ronson, Isaac Hayes and Toots and the Maytals to name but a few. He has also worked on soundtracks for feature films like 'The Rundown' and Washington Heights, as well as writing commercial scores for Apple Computer, Motorola, and Johnson & Johnson.